Bird flu was probably circulating in dairy cows for at least four months before it was confirmed to be the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus, according to a new analysis of genomic data by scientists at the US Department of Agriculture’s Animal Disease Center.

It adds to a growing pile of evidence suggesting that the H5N1 virus had a head start in the US dairy industry for months before it came to the attention of scientists and government regulators.

The USDA’s study was published as a preprint, ahead of peer review, on the BioRXIV server on Wednesday.

The USDA officially confirmed the presence of the H5N1 virus on March 25 in dairy cows in Texas.

At least one farmworker who was in contact with infected cows in Texas also tested positive for H5N1, the second human case of this type of flu ever reported in the US.

“If that had been done, that would have revealed H5N1 in January and then even beyond that,” he said.

The new study gives the USDA’s account of how bird flu seemed to spread so quickly to herds across the US.

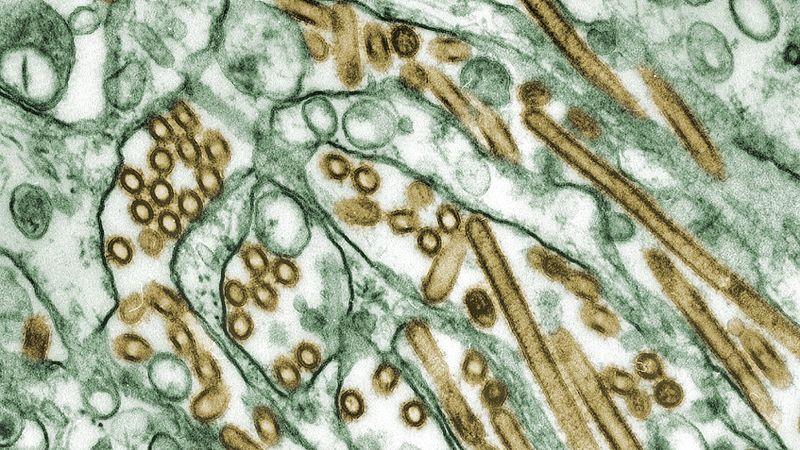

H5N1 has been devastating wild and domestic bird populations in the US since 2022, and it has infected a growing number of mammals.

Scientists at the US Department of Agriculture’s Animal Disease Center have conducted a new analysis of genomic data that suggests bird flu was likely circulating in dairy cows for at least four months before it was determined to be the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus.

Additionally, the study discovered infected cattle with no discernible link, indicating that “there are affected herds that have not yet been identified,” according to the study.

It is another piece of evidence that the H5N1 virus was operating in the US dairy industry months before scientists and government regulators became aware of it. This body of evidence is beginning to take shape.

The USDA’s study was made available on the BioRXIV server on Wednesday as a preprint, prior to peer review.

It comes after an independent, multinational team of nearly two dozen evolutionary and molecular biologists conducted a comparable analysis in which they expeditiously examined raw genome sequences that the government had uploaded to a National Library of Medicine server. That group reached almost the same conclusion as the USDA, despite the absence of important background information on those samples: the virus had spread from wild birds to cows between mid-November and mid-January, meaning it was in circulation for months before anyone realized.

On March 25, the USDA formally verified that dairy cows in Texas were infected with the H5N1 virus. Nine states have reported at least three dozen infected herds since then. The second known human case of this strain of flu in the US occurred in Texas, where at least one farmworker who came into contact with infected cows also tested positive for H5N1. Antiviral medication was administered to the worker, who has since recovered.

In a report released last week, the US Food and Drug Administration, tests of milk obtained from retail stores revealed inert remants of the virus in approximately 1 in 5 samples, indicating that the infection had spread widely. Experts have strongly advised against consuming raw milk, even though additional testing by the FDA has confirmed that the virus in the samples of pasteurized dairy products was not active and could not cause illness in anyone.

Dr. Michael Worobey, head of the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Arizona, who led the team of biologists that carried out the independent analysis, stated, “We could have done a much better job” of catching H5N1 in dairy cows. Worobey investigates the origins of pandemics.

Worobey said that ideally, a lab would have used a technique called metagenomic sequencing, which reads all the genetic material in a sample and uses computers to help pick out relevant information, instead of testing for specific viruses and bacteria as soon as the cows became noticeably sick with something mysterious.

He stated, “That would have revealed H5N1 in January and even beyond that if that had been done.”.

Worobey stated that regulators must alter their strategy if we’re serious about stopping animal outbreaks that might trigger pandemics in humans.

We must abandon the belief that sick animals or sick people are only the tip of the iceberg and take action now. Rather, he stated that in order to identify newly emerging pathogens, animals must be routinely tested using “modern techniques.”.

The latest study details how the bird flu appeared to spread so swiftly to US herds. This information comes from the USDA. Samples taken between March 7 and April 8 revealed that six poultry flocks in three states and 26 herds in eight states had very similar H5N1 viruses. This suggests that the virus spread in a single spillover event between wild birds and cows.

According to the study, “production veterinarians” first observed poor-eating cows in late January along with changes in the quantity and quality of their milk.

Since 2022, H5N1 has been wreaking havoc on domestic and wild bird populations in the United States and has spread to an increasing number of mammals.

The study discovered evidence that infected cattle had transferred the virus to domestic poultry flocks “through multiple transmission routes,” in addition to the movement between cattle and wild birds. The researchers also discovered that cats that resided close to dairy cows and a wild animal, a raccoon, were infected by the virus that is causing the current outbreak.

It’s interesting to note that the farmworker’s virus sequence differed significantly from the cow genomes in key ways. Scientists from the USDA came to the conclusion that the variations might indicate that samples from the animals the farmworker had interacted with were missing, or they might have resulted from the virus spreading from host to host.

According to Worobey, the findings indicate that H5N1 is “now seemingly well-entrenched in the dairy cattle population in the country” and may pose a long-term threat.

Let a virus establish itself in a population of domesticated animals, he said, and everyone is at risk, even though it’s far from certain that the virus will evolve in the right ways to cause a pandemic among humans.

“It does expand the list of species where these viruses can have the chance to find that ideal combination that allows them to wreak havoc in the human population, not just animals, but also one more species—a very important species—that didn’t have influenza A virus circulating in it before,” he said.