Beginning in the Stone Age, Neolithic herders descended into and occupied these vast tunnels, known as lava tubes, archaeologists have discovered.

Cooler air underground would have provided a welcome respite from the sun and wind, and for thousands of years, humans sheltered with their livestock in the tunnels.

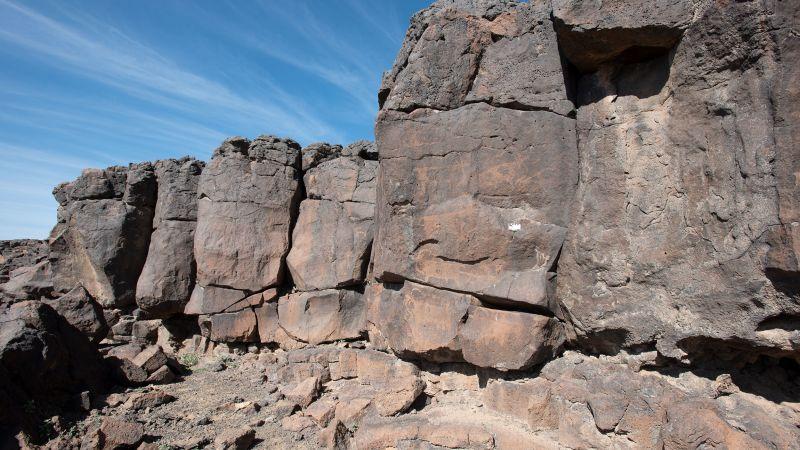

In the Harrat Khaybar lava field, about 78 miles (125 kilometers) to the north of Medina in Saudi Arabia is a tunnel system called Umm Jirsan, the longest in the region.

Scientists haven’t yet confirmed the age of the lava that formed this system, but a 2007 study suggested it was around 3 million years old.

Umm Jirsan spans nearly 1 mile (1.5 kilometers), with passages that are up to 39 feet (12 meters) tall and as much as 148 feet (45 meters) wide.

So the scientists turned their attention to Umm Jirsan.

Animal carvings In another tunnel near Umm Jirsan, the researchers found 16 panels of engraved rock art.

“Collectively, the archaeological findings at the site and in the surrounding landscape paint a picture of recurrent use of the Umm Jirsan Lava Tube over millennia,” Stewart said.

Tens of thousands of years ago, people who lived on the Arabian Peninsula sought refuge underground from the heat. According to a recent study, they may have stopped here on their journey between oases and pastures, diving into enormous underground tunnels where molten lava had once flown millions of years before.

Archaeologists have found that Neolithic herders inhabited and descended into these enormous tunnels, also known as lava tubes, starting in the Stone Age. For thousands of years, people stored their livestock in the tunnels because the cooler air beneath the surface would have offered a welcome break from the heat and wind. Researchers published their findings in the journal PLOS One on April 17, stating that the herders left behind artifacts and even carved pictures on the rocky walls.

The longest tunnel system in the region, Umm Jirsan, is located in the Harrat Khaybar lava field approximately 78 miles (125 kilometers) north of Medina, Saudi Arabia. Although the age of the lava that formed this system has not yet been confirmed by scientists, a 2007 study indicated that it was approximately 3 million years old. With passageways up to 148 feet (45 meters) wide and 39 feet (12 meters) tall, Umm Jirsan spans almost one mile (1 point five kilometers).

Not too long ago, 400–4,000 years ago, archaeologists at Umm Jirsan discovered animal bones, and 150–6,000 years ago, they discovered human remains. The first indication that humans were utilizing the tunnels, dating back at least 7,000 years, was discovered by the research team along with fragments of cloth, pieces of carved wood, and numerous stone tools.

Dr. Mathew Stewart, the lead study author and research fellow at Griffith University’s Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution, stated, “We knew that fossils were preserved at the site from earlier reports.”.

Through email, Stewart informed CNN, “Yet we were not anticipating to find evidence for human occupation in the form of rock art, lithic artefacts, stone structures, and pottery.”. For millennia, people inhabited and utilized these lava tubes. Although the majority of research conducted in Arabia focuses on surface sites, subterranean environments like Umm Jirsan have enormous potential to close some data gaps. “.

The importance of Umm Jirsan and other tunnels for comprehending human dispersal in the area is highlighted by this discovery, according to Guillaume Charloux, an archaeologist with the French National Centre for Scientific Research. According to Charloux, who studies ancient sites in Saudi Arabia but was not involved in the new research, there is generally little knowledge about the climate and human habitation in northwest Arabia in the Neolithic and early 2nd millennium.

According to his email, at this time, locals were congregating near newly created oases; the emergence of these desert havens would influence the region’s human migration patterns for millennia. “This creative and significant research project’s primary contribution, in my opinion, is that it highlights the long-term — presumably transient — use of this kind of cave, which had not been previously investigated, as well as their enormous potential, especially for comprehending paleoenvironmental contexts. “.

“Arabian Green.”.

The majority of the evidence of ancient human life in Arabia has come from sites near lake deposits, which Stewart and his colleagues have been piecing together for almost 15 years. Rainfall saturated the Arabian deserts starting about 400,000 years ago due to periodic periods of humidity. As a result of the abundance of lakes and ponds and the luxuriant vegetation that characterized these “Green Arabia” phases, waves of migratory humans spread throughout southwestern Asia, as previously documented by Stewart and colleagues in the journal Nature.

However, the last phase of Green Arabia ended about 55,000 years ago, and archaeological evidence is not very friendly to harsh desert environments. Although bone and other organic materials are easily eroded and destroyed by extreme heat and cold, as well as by erosion, stone tools do not preserve well in dry deserts, leaving little for researchers to interpret, according to Stewart.

“In order to better preserve organics and sediments, we decided to look into underground settings in 2019,” he said.

The scientists then focused on Umm Jirsan. The Saudi Geological Survey had previously mapped the area, and a 2009 report noted that it served as a haven for foxes, wolves, birds, and snakes among other wild creatures. Fragments of a human skull thought to be roughly 4,000 years old were among the bones found in the tunnel caches. However, Stewart noted that until 2019, archaeologists had not given the tunnel system much attention.

Stewart explained, “We were able to date the animal bones and sediments, which informed us that people began occupying the cave by 7,000 years ago and possibly as early as 10,000 years ago.”.

The amount of archaeological evidence at Umm Jirsan was “quite scant” in comparison to other places where humans have previously resided, the study’s authors noted, indicating that people were more likely to be transient residents rather than long-term residents of the tunnels.

Carved animals.

The researchers discovered sixteen panels of engraved rock art in another tunnel close to Umm Jirsan. The stick figures in the carvings seemed to represent herding scenes, with tool-wielding humans standing next to domesticated animals like sheep, cattle, dogs, and goats. Some carvings featured animals with horns that dramatically arched, resembling those of an ibex. However, the study suggested that these horned animals might be a different kind of domesticated goat. The subjects of the carvings and the varnish coating suggest that they are from the Chalcolithic period (c. 4500–3500 BC), a pre-Bronze Age regional period.

“When taken as a whole, the archaeological evidence at the location and in the surrounding area depict the Umm Jirsan Lava Tube’s repeated use over thousands of years,” Stewart stated. The location “may have served as a stopping off point, a place of refuge protected from the elements,” according to the site, which is situated along a known migration route for Bronze Age herders. “.

According to Stewart, additional research into Umm Jirsan and other lava tubes should yield even more information. The extraordinary evidence of human occupation in ancient Arabian lava tubes provides insight on how people adapted to live in arid environments.

“The natural and cultural archives that are still present in the archaeological record of Arabia have a great deal of untapped potential that these sites could potentially fill. “.

Science writer and media producer Mindy Weisberger’s writing has been published in How It Works, Scientific American, and Live Science.