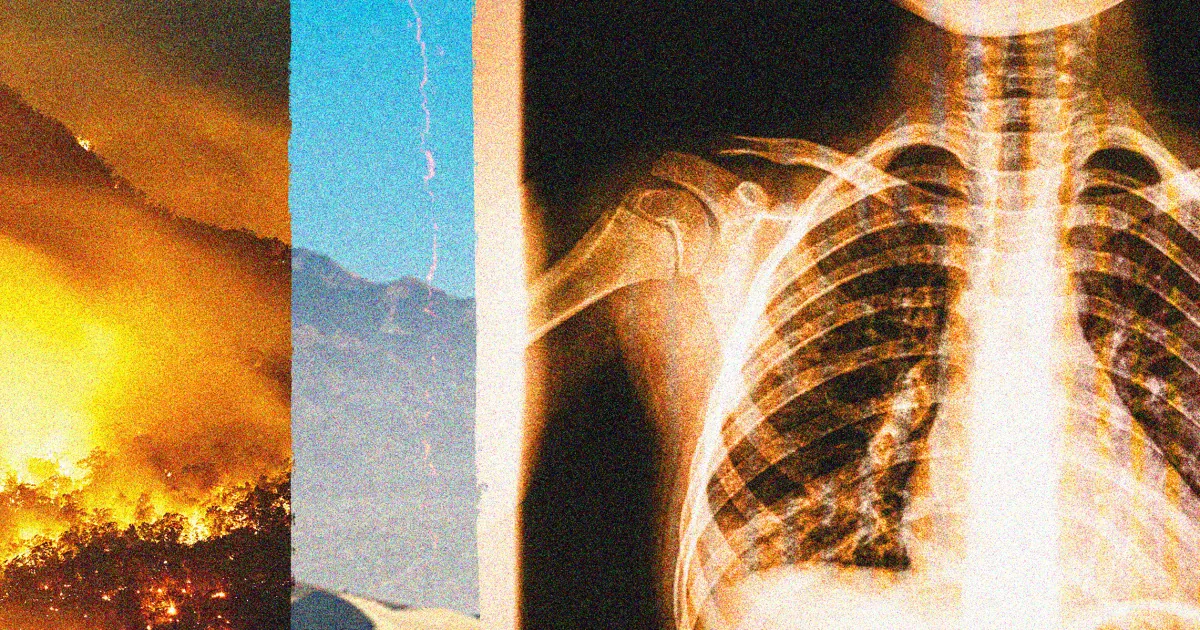

A biopsy of her spinal fluid revealed that Carrigan had coccidioidal meningitis, a rare complication of a fungal infection called Valley fever.

Valley fever is increasingly being diagnosed outside its usual territory and cases have been rising across the Western U.S.

This shift in weather patterns, which is driven by climate change, appears to largely influence where new Valley fever hot spots emerge.

In a 2023 study, researchers looked at 19 fires across California and observed higher rates of Valley fever following three of those fires.

“It’s not entirely clear whether there is a link between wildfires and Valley fever, but what is important to know is that coccidioides live in the dirt and anything that disturbs the dirt can exacerbate Valley fever,” Sondermeyer Cooksey said.

In April of 2024, Brynn Carrigan began to experience headaches. A few weeks later, she was severely disabled.

Her severe skull pain was made worse by her vomiting. She stayed in bed almost all the time, keeping the covers drawn over her head to block out any remaining light. Her microwave clock was too much, too.

Carrigan, 41, of Bakersfield, California, said, “I went from training for a marathon, raising two teenagers, and having a job to basically being bedridden.” Carrigan is employed with Kern County Public Health.

Her condition worsened, and the doctors were unable to offer any answers. However, on her third hospital visit, one of them asked her if she had experienced any respiratory symptoms prior to the onset of the headaches.

She had. Carrigan thought she had a normal cold about a month before the headaches began, but she remembered that her cough lasted a little longer than usual and that she later developed a rash on her thighs. Without treatment, both symptoms improved.

These proved to be important pieces of knowledge. Based on a spinal fluid biopsy, Carrigan was diagnosed with coccidioidal meningitis, a rare consequence of Valley fever, a fungal infection.

“I knew something was wrong, but I never imagined it would be this serious,” Carrigan remarked.

Spores of a fungus called Coccidioides, which is native to the hot, arid climate of the southwestern United States, are inhaled and cause valley fever, also known as Coccidioidomycosis. The range of the fungi is growing as a result of climate change, which is producing drier soils that are creeping farther east. The Western United States has seen an increase in cases of valley fever, and the disease is increasingly being diagnosed outside of its typical geographic range. S. . Every year, Arizona still has the most, but California is catching up.

California saw 1,500 to 5,500 cases annually between 2000 and 2016. These numbers increased to 7,700 to 9,000 yearly cases between 2017 and 2023. Preliminary data for 2024 indicates that there will be over 12,600 cases, which is the most the state has ever seen and roughly 3,000 more than the previous record set in 2023.

According to preliminary data, California is expected to set yet another record this year. As of right now, the state has recorded over 3,000 confirmed cases of Valley fever, which is more than the number at this time last year and almost twice as many as there were at this time in 2023.

“The number of coccidioidomycosis cases is definitely much higher than it was previously,” stated Dr. Royce Johnson, director of the Valley Fever Institute and head of the infectious disease division at Kern Medical in California. You would currently have to wait until July to see me, and the same is true for my coworkers. “”.

Cycles of drought are causing spread.

Carrigan is from Kern County, which is a arid, expansive area at the southern end of California’s Central Valley that is sandwiched between two mountain ranges.

The county has been the state’s epicenter for the fungal infection for the past three years, and it has already reported at least 900 cases of Valley fever this year.

According to epidemiologist Gail Sondermeyer Cooksey of the California Department of Public Health, however, the upward trend in California is not being driven by the persistently high number of cases in areas such as Kern County.

On the outskirts of the Central Valley, in the counties of Monterey and San Luis Obispo, along the central coast of California, new hotspots are instead starting to appear. So far this year, the number of cases in Contra Costa County, which is located just east of Berkeley, has tripled when compared to the same period in 2023.

Sondermeyer Cooksey stated, “It seems to be spreading out.”.

The effectiveness of Coccidioides spores’ multiplication and dissemination is probably influenced by a number of factors, but “drought is one thing we have identified as a big driver of those peaks and dips,” she said.

According to a 2022 study published in The Lancet Planetary Health, Valley fever cases are suppressed during drought years, but they sharply increase after several years of drought followed by a wet winter. The location of new Valley fever hot spots seems to be significantly influenced by this change in weather patterns, which is a result of climate change. The transmission season, when the spores spread, may also move from late summer and early winter to earlier in the year due to longer, drier summers.

“The Southwest is experiencing wetter wets and drier dries, but California is experiencing that to a greater extent,” said Jennifer Head, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Michigan who focuses on climate change and Valley fever.

New hot spots are emerging in Arizona, particularly in areas with a climate more akin to California’s than in other parts of the state.

Head stated that the northern plateau areas of Arizona, which have historically been wetter and colder like California, have seen the largest increases.

closely monitoring Los Angeles.

The same climatic patterns that are driving more intense wildfires are also spreading Valley fever throughout California. Although researchers are still figuring out how fires might increase the risk of Valley fever, some studies have linked wildfire smoke to an increased diagnosis rate.

According to Sondermeyer Cooksey, the state health department alerted first responders to the potentially elevated risk of Valley fever in the region due to the devastating fires that occurred in January in Los Angeles County. Outbreaks among wildland firefighters have previously occurred.

A small amount of evidence suggests that the spores of Coccidioides may be dispersed by wildfires. Three of the 19 fires in California that were examined in a 2023 study had higher rates of Valley fever after they were put out. These fires were typically larger, found close to populated areas, and burned in regions where Valley fever transmission was high before the fire.

Although the exact relationship between wildfires and Valley fever is unclear, Sondermeyer Cooksey stated that it is crucial to understand that coccidioides are soil-dwelling organisms and that any disturbance of the soil can worsen the disease. After fires, there are all the reconstruction projects that potentially disturb the soil. “”.

So far this year, Peak Valley fever season has not yet occurred. In regions affected by the fires in January, Sondermeyer Cooksey stated that state and local public health departments “are closely tracking the numbers” because reconstruction activities are uprooting soil in the burn scar.

Cases following the festival of Lightning in a Bottle.

The main reason Valley fever is difficult to diagnose is that its symptoms can be confused with those of other respiratory conditions like the flu, COVID, and pneumonia. According to Sondermeyer Cooksey, if someone has those symptoms, they should inform their doctor if they have been in an area known to have Valley fever or have been around disturbed soil or dust, such as a construction site, a campground, a hiking trail, an outdoor job site, or a festival.

People might not immediately connect the .s, according to Head of the University of Michigan, who stated that symptoms usually appear one to three weeks after exposure but can take up to eight weeks.

Later in the summer, at least 19 attendees of the Lightning in a Bottle music festival, which is returning to Kern County this month, were found to have Valley fever. There were at least eight hospitalized.

According to Dr. George Thompson, director of the Center for Valley Fever at the University of California, Davis, “Lightning in a Bottle is right in the middle of the endemic region, that’s one of the hot spots for the disease.” He added that while most attendees won’t become infected, those who aren’t from an endemic area may be more vulnerable.

According to Thompson, it is evident that he and his colleagues are treating more patients for the infection throughout the state. The fungus never leaves a person’s body once they are infected, but only around 1% of cases lead to potentially fatal meningitis or other complications like Carrigan’s did.

Johnson of Kern Medical stated that since there is no medication that can eradicate cocci, your immune system is what prevents you from getting sick. Antifungals are used to treat the infection “long enough for a person’s immune system to figure out how to control it.”. He stated that if you do something to interfere with that immunity, it may begin to grow once more and manifest years later.

Carrigan has been undergoing a rigorous course of antifungal treatments for the past year. She lost most of her eyelashes and hair in the first few months, and she hardly recognized herself when she looked in the mirror.

Even though she has fully recovered and completed a marathon this spring, she continues to take antifungal medication. According to Carrigan, she wants more people to be aware of the warning signs of Valley fever and the significance of informing their doctor if they have visited a location where cases have been reported. This could help people receive a diagnosis more quickly.

“Even if it’s just 1 percent of cases, the number of people who experience complications will rise along with the number of cases,” she stated.