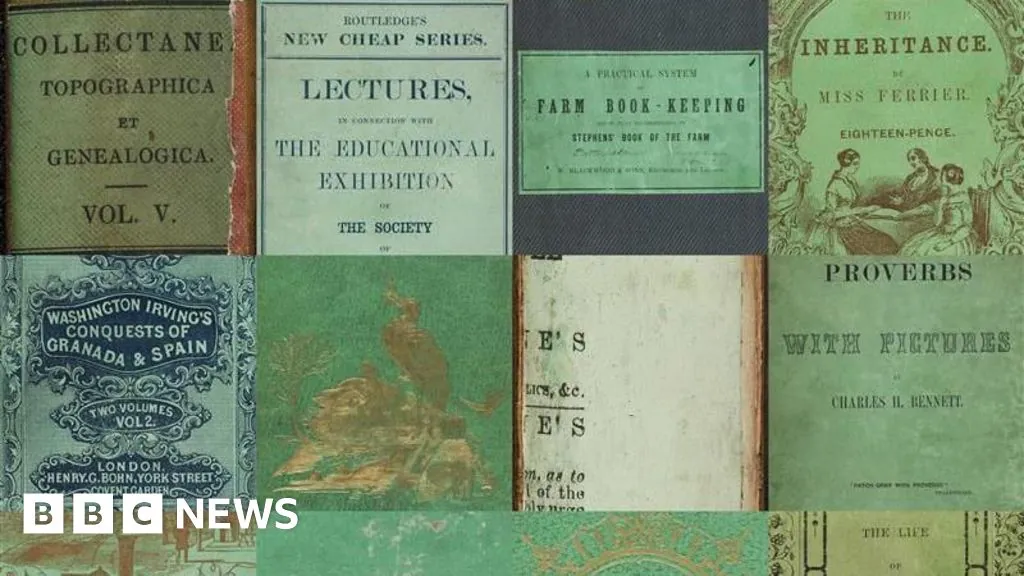

And unlike domestic items, books have survived in archives around the world, creating a 21st Century problem from 19th Century fashion.

Prolonged exposure to multiple green books can cause low level arsenic poisoning.

The Poison Book Project tested books and drew up a list of titles which are potentially harmful to humans.

“It uses green light, which can be seen, and infrared, which can’t be seen with our own eyes.

The green light flashes when there are no fragments of arsenic present, the red light when there are pigments.”

Four hours ago.

Michelle McLean.

Scottish Arts Correspondent for the BBC.

Green was adored by the Victorians. They particularly cherished a vivid emerald hue made by mixing copper and arsenic, which was utilized in everything from toys for kids to wallpaper.

According to Erica Kotze, a preservative conservator at the University of St Andrews, “this color was very popular for most of the 19th Century because of its vibrancy and its resistance to light fading.”.

“We are aware that a lot of household objects were colored with green pigments derived from arsenic. It even made an appearance in confections. “..”.

The issue, which persists over a century later, is that the mixture of elements used is toxic. This is especially problematic with old books.

To create eye-catching covers, Victorian bookbinders employed arsenic in addition to mercury and chrome. In addition, unlike household objects, books have survived in archives worldwide, posing a challenge to 19th-century fashion in the twenty-first century.

Multiple green book exposure over time can result in low-level arsenic poisoning.

Extended exposure can result in skin alterations, damage to the kidneys and liver, and a decrease in red and white blood cells, which can cause anemia and raise the risk of infection.

A partnership between the state university and the Winterthur Museum was established in Delaware in 2019 in an effort to address the issue.

After testing books, the Poison Book Project created a list of titles that might be dangerous to people. Four of these books were taken out of the French National Library right away.

This gave Erica Kotze the idea to visit Dr. Pilar Gil, a colleague who worked in Special Collections at the University of St Andrews after receiving training as a biochemist.

When surveying the thousands of old books in their collection, Dr. Gil adopted a pragmatic approach.

Finding a portable, non-destructive tool that could determine whether or not the book was poisonous was crucial, she says.

Because the books under examination were fragile, she ruled out X-ray technology and turned to the geology department instead.

They used a spectrometer, which is a tool used to measure the distribution of various light wavelengths, to find minerals in rocks.

Because “minerals and pigments are very similar,” Dr. Gil explains, “I borrowed the instrument and began searching books for emerald green.”. “..”.

After evaluating hundreds of books, she realized she was on the verge of a breakthrough.

“I came to see that the toxic ones followed a definite pattern. It was a “lightbulb moment.”. I realized that nobody had ever seen it before. “.

The physics department needed to be consulted in order to construct their own prototype.

How it operates is explained by Dr. Graham Bruce, senior manager of the research laboratory.

He explains, “It applies light to the book and calculates how much of that light bounces back.”.

The technology makes use of both visible green light and invisible infrared light. When there are pigments present, the red light flashes, and when there are no arsenic fragments, the green light flashes. “.

In comparison to a full-scale spectrometer, the new testing apparatus is smaller and will be less expensive to manufacture and operate.

Thousands of books in the National Library of Scotland and the St Andrews collections have already been surveyed using it, and the team hopes to share their design with other organizations worldwide.

As a large institution, we are fortunate to have expensive equipment that allows us to test potentially toxic books from the 19th century, according to Dr. Jessica Burge, deputy director of the University of St Andrews’ library and museums.

“However, we wanted to make something that was simple and inexpensive because other institutions with large collections might not have those resources. It’s instantaneous and doesn’t require advanced conservatory or analysis. “.”.

Furthermore, it is an issue that is not going away. Toxic books will only get worse as they age and decompose.

Once they have been identified, they can be safely stored and still enjoyed with restricted access and safety measures like wearing gloves.

“It will remain a live issue,” Dr. Burge states.

“But I believe that the largest problem facing institutions right now is that, because they are ignorant, any book with a 19th-century green cover is being restricted.

And as museums and libraries, that isn’t really our mission. Instead of limiting their use, we want people to be able to use the books and contribute to restoring access to collections. “.”.