In one scene, arrows were shot from a distance of 100 feet on a 40-foot elevation at two stunt men wearing wooden breastplates.

“A whale of a good story that has brilliant direction, writing and acting,” THR wrote in its 1939 review.

“The spectacular air stunts are done either by Frank Tallman and his Tallmantz Aviation stuntmen or by the actor themselves.

Director Douglas Hickox showcases a hang-gliding team led by Bob Wills and Chris Wills, with star James Coburn doing most of his own stunt work.

Welcome to the big time, Arnold.” 1983: Blue Thunder Photo : Everett Shot before the Twilight Zone disaster, the helicopter stunts attributed to the title chopper were meticulously mapped out and executed with precision.

Bill Jr., Steamboat, 1927–1928.

Everett took this picture.

It’s possible that Buster Keaton’s lifetime of (literally) death-defying stunt work has gone too far in this instance: a building’s side collapses on top of Buster, but his standing figure fits neatly into the upstairs window. He would have been flattened if there had been even the slightest measurement error or an unexpected wind gust.

Speedy, 1928-1929.

Everett took the picture.

The timeline is a little off in this entry, but Harold Lloyd, the four-eyed comedian, cannot be left out of any list of amazing stunts. Lloyd, or more accurately, his stunt double for the riskiest turns, speeds through New York’s streets in Speedy while riding a horse-drawn trolley. In an unforeseen mishap that is left in the movie, the trolley collides with an old IRT elevated subway pillar. The driver takes off. Variety stated that the horses’ survival was a miracle and that no one was harmed. Lloyd’s strength and agility throughout his “thrill films” are exceptional because, in 1919, he lost a thumb and finger from his right hand in an explosion (not a stunt) during a publicity shoot.

Dawn Patrol, 1929–1930.

Everett took this picture.

The flyers in Howard Hawk’s The Dawn Patrol (1930) were also flawless, but the obvious choice is the choreography of the biplanes buzzing like swarms of mosquitos in Hells’ Angels (1930). The nod goes to Hawks since all 46 of the stunt flyers who flew in his film’s combat simulation made it back to earth without incident.

1930-1931: The Enemy of the People.

Everett took the picture.

James Cagney, who played the title gangster, recalled, “This was before the special effects boys learned how to make ‘exploding’ bullets as safe as cap guns.”. A former WWI machine gunner off-screen started shooting as Cagney ducked down an aisle behind a “stone” wall. Cagney gulped, “The wall crumbled to sawdust, and so would I had I been there two seconds earlier.”.

The Air Mail, 1931-1932.

Everett took the photo.

The stunt flying in John Ford’s salute to the right stuff of aerial postal workers was hailed as “sensational,” “breathtaking,” and “hair raising” during a competition for supremacy in aerial acrobatics. The highlight occurs when a hotdog pilot buzzes an airfield and flies his biplane through a hanger three times.

1934: Villa Viva!

Everett is the photographer.

“Exciting as a bugle call, vibrant as a campfire flame, essential as the crimson pages that he lived, Pancho Villa marches again to the wild music of ‘La Cucaracha!'” blurred the New York American of Jack Conway’s biopic of the Mexican revolutionary, which is full of amazing horse-riding battle scenes and a true Vorkapich montage.

The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, 1935.

Everett is the photographer.

For 88 days, Henry Hathaway managed 1,200 people and innumerable horses across 40 studio sets and four locations. The film was infamously jinxed: star Franchot Tone fell twelve feet and was knocked out cold while fighting Gary Cooper, numerous stuntmen and extras hobbled away with broken bones, and animal trainer Melvin Scufe was hospitalized after being bitten by a camel.

1936: Zero Ceiling.

Everett took the picture.

No one was killed in another fantastic Howard Hawks aerial drama. Hawks once declared, “There is nothing more exciting on screen than an airplane taking off and landing.”. In its evaluation, THR gave Warner Bros. approval. manufacturing. The 1935 review of the paper stated that it was “an exciting comedy drama of commercial aviation which has the authentic feel of the game and is up to the minute in its display of the inside workings.”. “Masterfully crafted, expertly helmed, and performed by a superb ensemble of twenty, led by James Cagney and Pat O’Brien, this production is poised for significant returns on all fronts. “”.

The Hurricane, 1937.

Everett took the photo.

The Category 5 meteorological event that culminates John Ford’s South Sea adventure romance is brought to life by expert stuntwork, special effects, and professional actors. The way the “six 12-cylinder wind machines roared in deep-throated synchronicity to send showers of blinding spray about huddled groups of natives and tons of water were sent hurling down 65-foot inclines to engulf principles struggling in a tank below” astounded a breathless trade reporter. The eye experienced blind chaos as a result. Nobody lost their life.

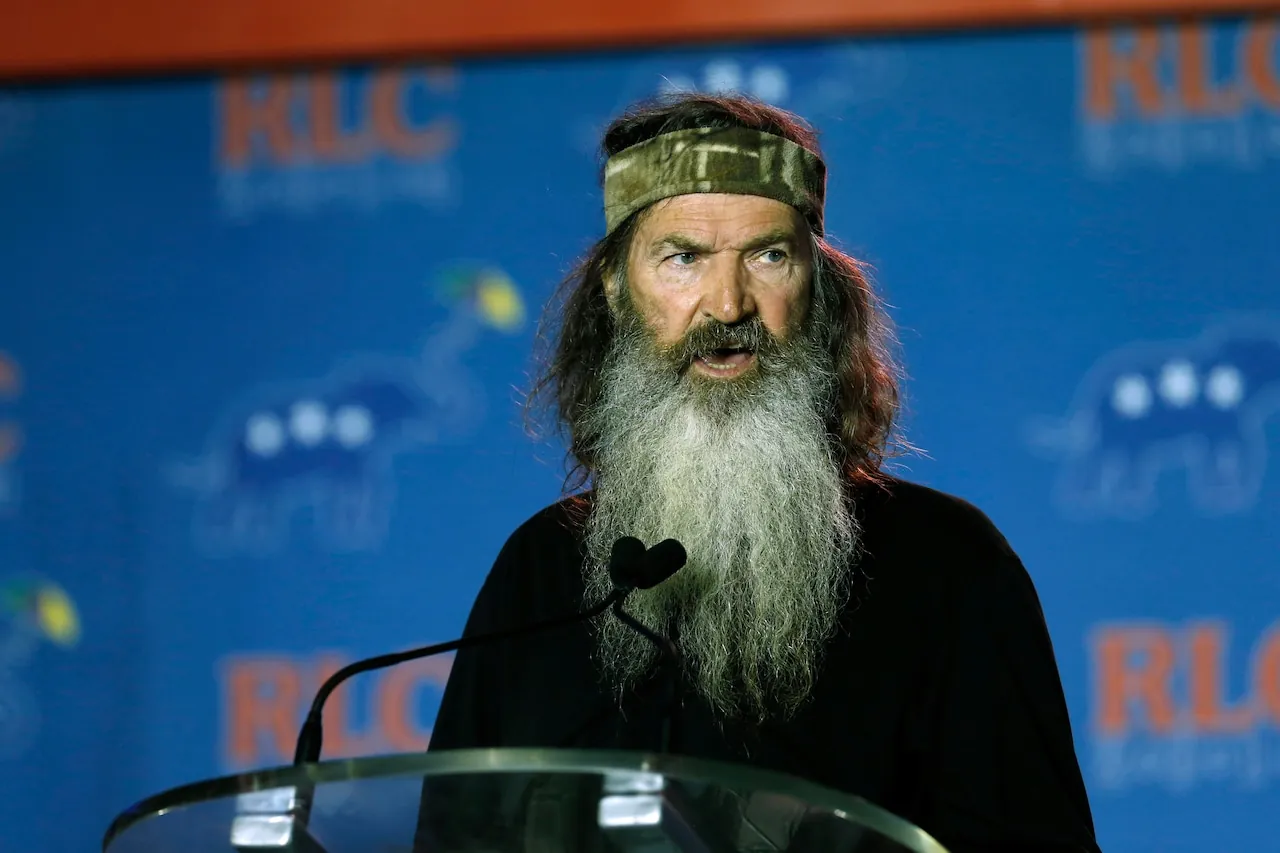

Robin Hood’s Adventures, 1938.

Everett took the picture.

With all those swords slashing and arrows flying everywhere, the Technicolor theatricality of Michael Curtiz’s men-in-tights antics may conceal how dangerous the atmosphere can get. Two stuntmen wearing wooden breastplates were the target of arrows fired from a distance of 100 feet on a 40-foot elevation in one scene. At the time, THR laughed, “The impact knocked the stooges flat.”.

Stagecoach, 1939.

Everett took this picture.

Yakima Canutt’s fall beneath a group of six stagecoach horses and the stagecoach continues to be the quintessential Hollywood stunt. He jumps from his horse at full gallop while dressed as an attacking Indian, landing between the two front horses pulling the stagecoach. When the stagecoach and the horses pass over him, he lets go and lies flat after falling between them and being pulled along the ground. It was impossible for Steven Spielberg to avoid reusing the stunt in Raiders of the Lost Ark [1981], substituting a truck for a stagecoach. Canutt regarded the stunt as his personal best; the word “stunt” seems too trivial. THR described it as “a whale of a good story with brilliant direction, writing, and acting” in its review from 1939.

Virginia City, 1940. .

Everett is the photographer.

In what THR at the time called a “sure-fire box office smash,” the prolific Michael Curtiz created one of Yakima Canutt’s signature stunts for this well-liked Errol Flynn western. Canutt doubles for Flynn by riding one horse in front of another. After his horse is shot and tumbles, Canutt snatches the other horse’s saddle horn and, in true pony express fashion, springs up into the second horse’s saddle. “This was an excellent joke, and I was surprised that I hadn’t come up with it myself,” Canutt remarked.

World War II, or Real Life, 1941–1945.

GIs who were not Screen Actors Guild members performed the most thrilling on-screen action during WWII in the newsreels and combat reports. THR wrote in December 1941, almost immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, “Hollywood will be called upon by the government to increase its efforts for the building of patriotism and boosting of the sales of defense bonds and stamps; the former will be achieved via motion pictures, and the latter by personal appearances and shorts.”.

Henry V., 1946.

Everett is the photographer.

Filmed in 1944 and directed by Laurence Olivier, the British import was a medieval war movie inspired by the ongoing mechanized conflict. It was released in the United States in 1946. The final battle was staged on St. Critics were thinking about the more recent firefight when they saw hundreds of knights on horseback in a Technicolor bloodletting on Crispin’s Day in 1415. Variety stated at the time that the British “won the battle with the atom bomb of the day, the longbow.”.

1947: Unbeaten.

Everett took the picture.

An incident that took place during Cecil B. The peril of even seemingly ordinary stunt work is demonstrated in DeMille’s frontier action adventure. On location at Cooks Forest outside of Pittsburgh, three stuntmen suffered serious injuries, as Variety sarcastically put it that year. A scene that required the men to swing from their horses, grab onto a limb, and vanish into the tree foliage was filmed, and the men were injured. Rather, they arrived at a medical facility. “”.

The Red River, 1948.

Everett took the photo.

Howard Hawks once more. Thanks to tens of thousands of cattle that appear deadly even when they are not stampeding and a battalion of dedicated horsemen, the famous 1,000-mile cattle drive from the Rio Grande to Abilene is reenacted with startling realism. As THR’s review put it, “The film would be notable on one count — if not other — the magnificent action material that is accomplished in the movement of the huge cattle herd across the western plains, an element of the story that reaches an electrifying climax.”.

She wore a yellow ribbon in 1949.

Everett is the photographer.

Ben Johnson, a former ranch hand who is now a stunt double and actor, leaps on a horse and rides off into the distance at a breakneck pace, combining man and beast like one in a stunning demonstration of equestrian skill captured by John Ford in a valorizing long take. It was described as “the finest outdoor picture produced in Hollywood for a very long time” in THR’s review. “”.

1950: The Arrow and the Flame.

Everett took the photo.

1951: The Women’s Journey West.

Everett is the photographer.

William Wellman should be more well-known for his female-focused western. It was described by THR at the time as “a big, sprawling, tremendously dramatic drama of pioneer days whose high artistic and dramatic content inevitably bracket it with such memorable outdoor narratives as Stage Coach.”. In order to reach the promised land of California—and their husbands—the frontier ladies must drive and drag their Conestoga wagons through rivers and over mountains with the help of Robert Taylor and a resilient group of stunt men and women.

1952: The Best Show in the World.

Everett took the photo.

The train wreck in Cecil B. captivated six-year-old Steven Spielberg. DeMille’s three-ring circus, but older audiences will be impressed by the risky closeness to elephants and the bold trapeze artistry. For the movie, DeMille boasted that his actors truly put their lives in danger. “A big, seething SHOW, spectacular, exciting, colorful,” was how THR described it in their review. Set against the captivating backdrop of billowing canvas, sawdust, bright-red wagons, calliopes, and people who live the life of circus mummers because they have no other choice, it is a powerful pageant. “”.

Mogambo 1953.

Everett took this picture.

John Ford’s Red Dust (1932) remake, which was filmed on location in Kenya (during a Mau Mau uprising), Tanganyika, Uganda, and what was then known as French Equatorial Africa and the Belgian Congo, makes it difficult to distinguish between an exploited “native bearer” and a stuntman. Only assistant director John Hancock, an Englishman, appears to have been mentioned in the trade press despite the fact that three of the crew perished in traffic accidents.

The Creature of the Black Lagoon, 1954.

Ricou Browning performed the majority of the Gill-Man’s underwater scenes, holding his breath for as long as four minutes, alongside Ben Chapman. THR described it as “a good piece of science-fiction of the beauty and the beast school,” with the beast in this instance being a hideous hybrid of a fish and a man. It is an excellent source of horror-thrill entertainment.

The Man from Laramie (1955).

Everett took this picture.

Among all the traditional Hollywood genres, westerns had the greatest negative impact on both humans and animals. While riding a horse on the Devil’s Backbone ridge in this Anthony Mann western, stuntman Frosty Royce suffered a heart attack. He was finally compelled to hang up his spurs at the age of forty-three, after twenty-three years in the industry.

1956: Peace and War.

Everett took this picture.

Although Dino De Laurentiis and King Vidor’s VistaVision spectacle appears to be nearly as long as Tolstoy’s novel at three and a half hours, the stunts and second unit work are amazing. In a review published at the time, THR stated that the production “will stand up to comparison with the great ones and is on a lavish scale comparable only to a handful of motion film pictures in history.”. The actions of thousands of men and horses, the portrayal of Moscow’s devastation, the evacuation and occupation of the city by Napoleon’s army, and the final catastrophic French retreat across thousands of miles of charred and frozen earth left Motion Picture Daily speechless. “”.

The Bridge on the Kwai River, 1957.

Everett took the picture.

David Lean’s epic, set in a Japanese prison camp during World War II, was filmed in hot Sri Lanka in conditions that the cast and crew only vaguely compared to the original. In the final bridge explosion, a stuntman and a prop man almost drowned. The end result was a film that received a lot of positive reviews. THR wrote in a review that it was a “magnificent war epic,” stating that “if ever there was a nearly perfect motion picture in every way, this Sam Spiegel production for Columbia is it.”.

Thunder Road, 1958.

Image: Embed.

Prior to Burt Reynolds’ robbery, Robert Mitchum smuggled moonshine through Appalachian back roads, leaving Treasury Department agents in the shade. Mitchum argues that a man has the right to produce whiskey on his own property. THR wrote, “Carey Loftin’s inventiveness in arranging the thrilling chases and car crashes ranks him high among Hollywood’s stunt men,” recognizing a player who is frequently disregarded.

Ben-Hur (1959).

Everett took this picture.

Once more, in her harness as a stunt coordinator, Yakima Canutt trained Stephen Boyd, Charlton Heston, and 80 Yugoslavian horses to master a sport that hasn’t been played in a coliseum since the Vandals sacked Rome in 455 AD, or at least not since the previous MGM version in 1925. “A prodigious array of breathtaking spectacle, wonder, splendor, unforgettable sights, and sound are all evident on the screen in an unprecedented $15,000,000 production cost,” THR continued in its review. Up to 8,000 extras are on screen at once, in addition to hundreds of horses, African camels, fifty ships constructed especially for the sea battle, eighteen chariots, and three hundred sets that recreate the splendor of Rome and the majesty of Jerusalem. There is no comparable level of technical and physical production. “.”.

While both Ben-Hur versions showcase stunning horsemanship and charioteering, the Wyler version wins the stunt race not only for its full-color, widescreen display but also for not putting an estimated 100 horses to death like the previous version did. Canutt pulled Heston aside saying, “Chuck, you just stay in the chariot and you’re going to win the damn race,” because Heston was training so hard with reins and a whip. “.”.

1960: Spartacus.

Everett took this picture.

There is amazing stunt work throughout Kirk Douglas and Stanley Kubrick’s non-biblical spectacle, including the gladiator bouts and pitched battles, but Clifford Stine’s amazing shot of 8,000 Spaniards portraying Roman warriors makes it feel like you’re watching a documentary from 71 BC. In its review, THR stated, “It is a magnificent picture, spectacle to dazzle the eye, political conflict to tease the mind, innocence to hug the heart.”. It is estimated to have cost $12,000,000, so Spartacus will not receive its money back the day after tomorrow. However, it is a good accomplishment, a wise long-term investment, and it will be a huge attraction. “.”.

El Cid. 1961.

Everett took this picture.

Charlton Heston and Yakima Canutt once more. Shot over five days under the direction of stunt coordinator Enzo Musumeci Greco, Anthony Mann directed this reverent biopic of the Castilian nobleman from the eleventh century, which was energized by Canutt’s second unit work and an epic duel between Heston and Christopher Rhodes. The most improbable stunt in the movie, according to critics, was how El Cid led the last battle while dead and strapped to his horse.

1962: The Winning of the West.

Everett took the photo.

The CineRama epic, which had three directors (George Marshall, John Ford, and Henry Hathaway each did one section), features a railroad wreck, rafts spinning through river rapids, and buffalo stampedes. The cost was high: during the train scene, Yvonne De Carlo’s husband, stuntman Bob Morgan, almost lost his life in an accident.

1963: The Great Escape.

Everett took the photo.

In the WWII prison camp film directed by John Sturges, a 60-foot motorcycle jump is launched from the undulating hills of Bavaria. In the medium and close-up shots, Steve McQueen is clearly holding the Triumph TR6 Trophy, while in the long shot, stuntman Bud Ekins actually makes the jump. In a 1998 interview with Cycle News Magazine, Ekins claimed, “I made it on the first pass,” and that he received $1,000 for the stunt.

Zulu in 1964.

Everett is the photographer.

Though it may be problematic by today’s standards, Cy Endfield’s contentious portrayal of the 1879 conflict between 4,000 Zulu warriors and about 100 fearless British soldiers is captivatingly realistic in its portrayal of spear-versus-rifle battles, and the Zulu tribesmen who were chosen for the movie do their ancestors justice.

Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, 1965.

Everett took this picture.

With its catchy title, director Ken Annakin’s bizarre historical drama transports viewers to the pre-Great War era of aviation in 1910. Box Office wrote, “The real stars of the picture are such antique aircraft as Demoiselle, Bristol Box Kite, Avro Triplane, and other flying oddities.” However, the other real stars are the amazing men who fly the “spit and baling wire” aircraft, such as Air Commander Allen H., an ex-RAF man and “old plane nut.”. “I’ve flown countless aircraft through the sound barrier, but this is a bit more fun,” joked Wheeler. “”.

Naked Prey (1966).

Everett took the photo.

In the naked and terrified pursuit movie, which was filmed on location in Africa, producer, director, and star Cornell Wilde endures a lot. For the squeamish, no.

1967: The Grand Prix.

Everett took the photo.

James Garner driving at 140 mph, car-sickening helicopter shots, and radio-controlled Super Panavision cameras are all features of John Frankenheimer’s documentary-style race car movie. Milt Rice, a special effects artist, “devised an air cannon that could catapult a car (minus engine) 200 yards in 2 seconds,” according to an account of the filming and stunt work in American Cinematographer. He also created somersaulting race cars.

Bullitt (1968).

Everett took this picture.

You can see from the above that this was a pick. At the time, THR praised the famous sequence, saying, “One gasping 11-minute chase sequence packs more excitement than anything since the second Ben Hur chariot race.”. Few movies even dare to promise the leader-to-leader bravura action that Bullitt delivers without sacrificing logic or morality. The movie is not likely to make enough money to turn a profit, but it should still be a huge hit and a box office success. “”.

The Gypsy Moths (1969).

Everett took the photo.

The most amazing aspect of John Frankenheimer’s stillbirth melodrama is the amazing skydiving, which was captured by aerial photographer Carl Boenish and visual effects specialist J. Lewis Carroll and McMillan Johnson. Shepphird. The other kind of stunt was staged for the movie’s Hollywood premiere: three skydivers dropped 3,500 feet with smoking flares and made a precise landing in the parking lot of the Pacific Cinerama Dome Theater.

1970: “Tora!” “Tora!”.

Everett took this picture.

The original ordnance could be called back up for duty and photographed in the real world, which makes the postwar WWII spectacles as exciting as the biplanes called back into action for the postwar WWI aerial films. Beginning with the Japanese-U. A. Based on a real-life incident, the coproduction features a thrilling scene in which a flying instructor is teaching a student in the early morning when her plane is caught in the middle of a flurry of Japanese zeroes that fly into frame.

Vanishing Point, 1971.

Everett took the picture.

The obvious choice is the car chase in The French Connection, but take a road trip with Richard C. to get a taste of the car crashes, amphetamines, and gratuitous nudity that characterized a rich substratum of 1970s cinema. A new generation was introduced to Quentin Tarantino’s drive-in cult classic, Sarafian.

Deliverance in 1972.

Everett took the photo.

Jon Voight and Burt Reynolds risked their lives riding the rapids during John Boorman’s terrifying backcountry hunting expedition. “I went out and got Jon Voight after paying Burt $50,000. In 2018, Boorman told THR, “They were complete opposites.”. In order to avoid being bothered by signing autographs, Jon detested doing so. Burt claimed to love it and could do it all day. Burt took the approach of looking at a scene and asking himself, “How do I get through this without making a fool of myself?” whereas Voight examined every detail in great detail.

Papillon, 1973.

Everett took the photo.

J. Franklin. Locations in Jamaica and Spain are transformed into a realistic representation of the hell on earth that was serving time in French Guyana in Schaffner’s gritty prison film. The money shot shows Steve McQueen jumping into the ocean from a cliff off Maui. In its review at the time, THR also noted that “Papillon sometimes seems like a majestic silent film, filled with staggering images of jungle, prison, ocean, and sky.”.

Inferno in the Towers, 1974.

Everett took the picture.

Paul Stader, the stunt coordinator for Irwin Allen’s quirky disaster movie, declared, “Fire is a dangerous co-star in a movie stunt.”. Thankfully, new developments in Nomex, a synthetic material that resists flames, have made it possible for “one stunt man to burn two or three times longer than ever before, and I only worry half as much about their safety.”. The fire and explosion scenes rely on the mechanical effects of A, according to THR’s critical evaluation. D. Herman Lewis’s sound, Flowers and Logan Frazee, and Paul Stader’s stunt coordination—which includes the most realistically staged burning human bodies ever for the camera—are all noteworthy. “.”.

This is The Great Waldo Pepper from 1975.

Everett took the photo.

George Roy Hill’s part nostalgic, part terrifying Robert Redford film, which takes place in 1926–1931 during the great age of barnstorming biplane aerial acrobatics, recruited pilots who were not trained during the Great War to perform aerodynamic stunts that were first created in the Jazz Age. “Hill is looking for staging that is authentic.”. In its review, THR stated, “There are no process shots.”. Frank Tallman and his stuntmen from Tallmantz Aviation or the actor themselves perform the amazing air stunts. Redford appears to be flying straight ahead, with no back projection behind him. “”.

Sky Riders from 1976.

Everett is the photographer.

According to THR’s review of the 1976 story, “Sky Riders conceives a familiar kidnapping-by-terrorists plot but with a clever twist — the rescuers reach the isolated mountain hide-out with hang gliders.”. Star James Coburn does the majority of his own stunt work, and director Douglas Hickox presents a hang-gliding team under the direction of Bob and Chris Wills. The trade went on to say, “The photography of Ousama Rawi is especially noteworthy because it captures the hang gliding scenes.”. “.”.

1977: The Bandit and Smokey.

Everett took the photo.

As a pilot of Burt Reynolds’ Trans Am across the Mulberry Bridge, Hal Needham once again became a stuntman. According to THR’s review, “the film is mildly entertaining — and completely mindless — due to a number of humorous sequences that are combined with some exciting road action.”. Hal Needham, who makes his directorial debut following a distinguished career as a stuntman, makes the most of the action and moves the plot along with the ideal amount of humor. “”.

Olly Olly Oxen Free (1978).

Everett took this picture.

Listen to me: we shouldn’t undervalue the bravery of seventy-year-old Katharine Hepburn. “That man doesn’t even look like me!” Hepburn sneered (and you can hear her say it) when she was shown her would-be stunt double. THR explained what happened next: “The irrepressible Katharine Hepburn steadfastly did all her own stunt work on the picture, which required her to hang midair over a body of water on an old ship’s anchor, climb up a rope ladder into a traveling hot air balloon, put out a fire by smothering it with her own body, and, finally, descend in a traveling balloon over the Hollywood Bowl with an audience watching as the Los Angeles Philharmonic played the ‘1812 Overture. ‘.

The End of the World (1979).

Everett took this picture.

Francis Ford Coppola’s journey into the heart of darkness features helicopter pilots of the Philippine Air Force flying in cavalry formation to Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyrie” and incendiaries exploding in dreamy rhythm to the Doors. As the film moves on to the GI show, the bridge attack, and finally the arrival at Kurtz’s Cambodian compound, THR noted in its review at the time, “we become increasingly aware that we are seeing a very special kind of imagery — where lights, settings, and people are all meticulously choreographed, almost as an opera, for their fullest visual impact; while at other times, in the film’s more intimate moments, that same enormous screen may be filled by a single head — Sheen’s, Brando’s — peering at us directly through the lens of the camera.”. “.”.

From 1980: The Stunt Man.

Everett is the photographer.

Steve Railsback plays the title character in Richard Rush’s wheels within wheels portrayal of Hollywood illusion making (the stunts in the movie are being mounted for a spectacle and, of course, for The Stunt Man). Perhaps, in keeping with the film’s conceit, it alludes to stunt coordinator Grey Johnson. Film critic Arthur Knight wrote in THR at the time, “To be honest, I think Rush has done an amazing job of making all this work, walking the fine edge between madness and melodramatics.”. Grey Johnson’s stunts are not only thrilling, but we are often given behind-the-scenes looks at how they were planned and executed. The scale of this movie within a movie (a World War II film) is just this side of epic. “”.

The Road Warrior (1981).

Everett took this picture.

Mel Gibson driving the final V-8 interceptor in George Miller’s death races in the post-apocalyptic outback offered the ideal reward for the 1970s car chase sweepstakes thanks to their increased vehicle velocity. Miller orchestrates all types of motorized mayhem, collisions, and sideswiping during this highway odyssey, which turns into a never-ending battle on wheels, according to THR’s review. “The sheer thrills leave one speechless.”. “”.

The Barbarian, Conan (1982).

Everett took this picture.

The fantasy/swords and sorcery action-adventure and medieval weapons clash in John Milius’ flesh appears to be lethal, but amazingly, the only actual bloodletting was a cut finger. “The title role is a perfect fit for Schwarzenegger, and it has the potential to propel him into the upper echelons of today’s cinematic adventure heroes,” THR wrote in its review. “He consistently demonstrates star quality, has a winning rapport with the camera, and has the perfect balance of vulnerability and chiseled brawn.”. even though his torso was covered. Welcome, Arnold, to the big time. “”.

1983: Blue Thunder.

Everett took this picture.

The title chopper’s helicopter stunts, which were filmed prior to the Twilight Zone catastrophe, were carefully planned and performed. Despite the abundance of process and rear screen shots, Jim Gavin and an experienced group of pilots piloted a real helicopter, a 1973 French five-seat executive helicopter that had been modified.

Against All Odds (1984).

Everett took the picture.

Known at the time as “the best piece of stunt work since The French Connection,” the race between Jeff Bridges’ 911 SC Porsche and James Woods’ 308 GT Ferrari took place in downtown Los Angeles. Although the agreement with automakers forbade any collisions, Taylor Hackford directed and stunt coordinator Gary Davis planned out the racing action. According to Davis, “we had to spice it up with a lot of near misses without causing any wrecks.”. In its evaluation, THR also noted that “today’s Mean Streets may likely be Century City corridors.”. “”.

To Live and Die in L., 1985. 1.

Everett is the photographer.

William Friedkin somehow wins the car chase in The French Connection by making a slick turn down the 405 (the Terminal Island Freeway near Wilmington, California), which is every Angeleno’s worst driving nightmare. According to THR’s review, the technical aspects of the production were praised: “While it is meant as no slight to the performers’ excellent portrayals, the star of To Live And Die In L. a. unquestionably the technical credits. Indeed, a striking, brutal, and exquisite portrait of corruption has been painted by Friedkin and his team. They have pierced the veneer to reveal the darker side of institutional integrity and human nature. ”.

1991: Judgment Day in Terminator 2.

Image courtesy of Tri-Star Pictures.

In his high-tech sequel to the low-tech noir The Terminator, James Cameron introduced a number of digital morphing effects that were unprecedented at the time. However, for the breathtaking stunt involving a helicopter and the California transportation system, Cameron returned to analog. Arnold Schwarzenegger joked that the catering bill for the sequel would have financed the original. The video and Cameron’s commentary track have been making the rounds on social media lately. He asks, “Do you see this helicopter passing beneath the freeway overpass?”. Helicopter passing beneath a freeway overpass is what that is. Chuck Tamburro was pilot.

1992: The Death Weapon 3.

Everett took this picture.

Typical of the action-adventure cops and robbers chaos of its era, Richard Donner’s buddy movie explodes in its third installment. “Director Donner keeps complete control throughout, speeding through crazy action sequences and deftly braking for comedic and intimate moments,” THR concluded at the time. “Despite its tight budget, Lethal Weapon 3 is a masterfully paced entertainment piece that is enhanced by incredibly potent technical work, particularly Jan De Bont’s blazing cinematography. “.”.

Cliffhanger, 1993.

Everett took the photo.

Yikes—the aerial transfer between two planes, in which stuntman Simon Crane slides on a steel cable, is positively Cruisian in its are-you-blanking-kidding-me audacity. The mountain climbing sequences in Renny Harlin’s suspenseful film, which was filmed in the Italian Dolomites, which mimic the Rockies, are just frightening.

Speed, 1994.

Everett took this picture.

The appropriately named tense romance, which takes place on a city bus—an exotic setting for many Los Angelenos—never slows down below fifty miles per hour. A 75-foot bus jump was the daring stunt, and Bill Young, not Sandra Bullock, was the precise driver. “Director Jan De Bont (the cinematographer of Die Hard and The Hunt for Red October), making his feature debut, expertly builds tension and uncorks magnificent scenes of vehicular mayhem,” wrote THR in its review. The film’s amazing wide-screen imagery, superb editing, and outstanding sound design deserve praise from the pedal-to-the-metal production team. “.”.

1995: GoldenEye.

Everett is the photographer.

An unassailable decision: stuntman Wayne Michaels’ 220-meter bungee jump plunge from the summit of Switzerland’s Verzasca Dam, which sets off the action in the seventeenth installment of the James Bond series. THR wrote in its review of the Bond entry, “GoldenEye is two hours of well-executed thrills, high-tech mayhem, and one-of-a-kind comedy,” with a dynamite opening reel that showcases the series renewed vigor. “Director Martin Campbell’s film features action scenes that are intense, edgy, slightly bloodthirsty, and teasingly sexy. “”.

1996: Bravery Amid Adversity.

Everett is the photographer.

The scene that almost gave producer David Friendly a heart attack is worth watching. “Denzel Washington’s character was filmed before the stunt, bailing out of the car and walking off the tracks,” Friendly told THR in 2014. The vehicle then struck the train while a dummy was behind the wheel. Denzel should have been farther away, but the actor in him told him to get close enough to get both the car and himself in the picture when the blowback pushed the Mustang fifty yards back down the tracks. I was frightened to death. “.”.

1997: The Titanic.

Everett took the photo.

Not since Noah’s Ark (1928) by Michael Curtiz had so much water poured on so many people at such a high pressure and speed. Curtiz sent everyone to the hospital, but Cameron didn’t. According to THR’s review, “The Titanic’s visual and special effects transcend state-of-the-art workmanship, invoking feelings within us not usually called up by razzle-dazzlery.”. Best wishes to Thomas L., the special effects coordinator, and Rob Legato, the visual effects supervisor. Fisher for the strong, decisive imagery. It’s often awesome, most prominently in showing the ship’s unfathomable rupture. The splitting of the iron monster is a heart stopper, in no small measure compounded by the sound team’s creaking thunders. ”.

1998: Ronin.

Getty Images/United Artists.

John Frankenheimer’s thriller eschewed fakery. “Every stunt, car chase, and wreck was done live in the camera instead of digitally,” boasted Larry Gleason of MGM. About 300 stunt drivers were employed by Frankenheimer to maintain traffic flow.

1999: The Matrix.

Everett is the photographer.

The wire walking martial arts ballets and the gravity-defying bullet time FX compete in red pill/blue pill fashion for pride of place in the only partially computer-generated wonder world conjured by Lana and Lilly Wachowski and fight choreographer Chad Stahelski. “Word-of-mouth will be giddy,” THR predicted in its review, “with young and mature males lining up for a technologically stunning movie that furthers the genre and features crowd-pleasing performances to go with the frequent scenes of gunplay and violence. ”.

2000: Gone in 60 Seconds.

Photo : Everett.

When the calendar page turned over to a new century, low attention span editing, CGI, and in-camera speed adjustments began to define the car-centered action adventure. Fifty luxury vehicles whoosh by in Dominic Sena’s grand theft auto-esque heist film.

2001: The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

Photo : Everett.

Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, whose clash of armies in Middle Earth were often staged in Real World Earth, saw stunt people and extras alike hobbling off the battlefield due to an over exuberant commitment to character. The indispensable performer was 4-foot two-inch stunt man Kiran Shah, who was responsible for the heroics of more than one full-sized actor playing a Hobbit.

Honorable mention for the year: Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes reimagining. Because every stunt is more difficult in an ape costume, especially on horseback.

2002: The Bourne Identity.

Photo : Everett.

Any franchise that has inspired a theme ride at Universal Studios warrants an inclusion. Like William Friedkin, helmer Doug Liman wanted to go bumper to bumper with The French Connection with a Mini Cooper in the streets and stairs of Paris. Stunt coordinator Nick Powell defied the French rules of the road. Added THR in its review, “the Doug Liman-directed movie does capture the pulp verve of those 1960s Cold War thrillers directed by the likes of Guy Hamilton and Terence Young. ”.

2003 and 2004: Kill Bill Vol. 1 and Kill Bill Vol. 2.

Photo : Everett.

Quentin Tarantino’s back-to-back homage to martial arts revenge films of the 1970s — do not call them “chop-socky” — features high-wire flying, flipping, and slicing, notably when the Bride deftly dispatches the Crazy 88s, with stunt woman extraordinaire Zoë Bell stepping into Uma Thurman’s jumpsuit for the more demanding maneuvers. “In the beginning, I was saying to Quentin, ‘We’re never going to get this in under two and a half hours,’” producer Lawrence Bender recalled to THR in 2023. “And he argued with me, and he said, ‘It’s going to be fine. ’ We had these arguments, and finally he says to me, ‘You just have to trust me. ’ I said, ‘OK, I trust you. ’ And as the shoot went on and on and on and on and on, it became clear toward the end that there’s a possibility this could end up being two movies. We didn’t go into it as two movies. ”.

2005: Mr. and Mrs. Smith.

Photo : Everett.

Doug Liman’s battle of the sexes fuels a pure popcorn film that makes no attempt to hide its reliance on rear screen projection for the driving scenes (a technique “as old as filmmaking itself,” admits cinematographer Bojan Bazelli) and use of stunt doubles (Eunice Huthart and future director David Leitch), but the compensation is the sight of Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, both at peak gorgeousness.

2006: Jackass Number Two.

Photo : Everett.

Don’t try any of this at home, kids.

2007: Death Proof.

Photo : Everett.

Elsewhere on the marquee, digital effects were supplanting and corrupting real world stunt work, but Quentin Tarantino was “all about old school” in his homage to Vanishing Point. Kiwi actress, stuntwoman, and absolute force of nature, Zoë Bell is strapped supine on the hood of a 1970 Dodge Challenger with Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell) in hot pursuit in a vehicle that, he will discover, does not quite make him death proof.

2008: The Dark Knight.

Photo : Everett.

“The stunt work in The Dark Knight looks like it is happening on the streets and not in the computer,” commented THR at the time, and that’s because, for the most part, it was. Christopher Nolan would much rather crash a real Lamborghini, flip a real truck, or blow up a (mostly) real hospital building than cheat with software.

2009: The Taking of Pelham 123.

Photo : Everett.

Tony Scott’s remake of the 1974 subway-set heist film faced formidable logistic and stunt challenges, including, as American Cinematography noted, “noise, dirt, darkness, the 600-volt third rail, and the bureaucracy of New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority. ”.

2010: Unstoppable.

Photo : Everett.

Speed on train tracks — above ground this time — was, said director Tony Scott, “the most dangerous movie” he had ever made, mainly due to his insistence on live action stunts on a locomotive running 70 mph. “Chris Pine and myself are just sidemen for the train,” semi-joked Denzel Washington about his co-star and him.

2011: Drive.

Photo : Everett.

Nicolas Winding Refn’s ice-cold crime drama is about a stunt driver who moonlights as a getaway driver for bank robbers who presumably cannot drive a stick. Rather than careening through traffic in conspicuously flashy sports cars, he knows that sometimes the best way to escape from the cops is to drive the speed limit in vehicles with a familiar make.

2012: Skyfall.

Photo : Everett.

As with the Bourne franchise, it seems reasonable to limit the number of entries allotted for the various iterations of the Bond franchise, but the motorcycle race over the rooftops of Istanbul, with Robbie Maddison doubling for Daniel Craig, cannot be omitted. Sam Mendes directs it like a Fitzpatrick travelogue on speed. “Dramatically gripping while still brandishing a droll undercurrent of humor, this beautifully made film certainly will be embraced as one of the best Bonds by loyal fans worldwide,” praised THR in its review, “and leaves you wanting the next one to turn up sooner than four years from now. ”.

2013: Fast and Furious 6.

Photo : Universal.

Yes, by 2013, the series had definitely reached its baroque phase, but the flip-car sequences by Dennis McCarthy, done in life not CGI, are forever jaw dropping.

2014: John Wick.

Photo : Everett.

Directed by former stuntman Chad Stahelski along with David Leitch, the first of the franchise has the requisite fisticuffs and gunfights performed by the experts. “If I’m doing it, it’s not a stunt,” said Keanu Reeves. “Stunt men do stunts. ”.

Added THR in its initial take, “Distilling a couple of decades of stunt work and second-unit directing experience into 96 minutes of runtime, Stahelski and Leitch expertly deliver one action highlight after another in a near-nonstop thrill ride. With a tendency to favor skillfully framed master shots over quick cuts from multiple angles, they immerse viewers in dynamic onscreen clashes that recall John Woo’s classic bullet ballets with an overlay of emotional intensity. ”.

2015: Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation.

Photo : Everett.

Throw a dart at the Tom Cruise catalogue and you’ll hit a clip of some of the best stunt work ever recorded on film. In this one, he hangs from the side of a plane during takeoff. Seriously. “The formula of ingredients is familiar and time-tested, to be sure, but some cocktails go down much better than others, and McQuarrie and company have gotten theirs just right here,” THR wrote in its review. “The protagonists‘ dilemmas are quite extreme, the surprises come in all sizes and the ultra-smooth professionalism displayed in all departments early on encourages the sense that you’re in good hands, a feeling that ends up being justified. ”.

2016: Hacksaw Ridge.

Photo : Everett.

Mel Gibson’s World War II film is ostensibly in service to conscientious objection, but the vivid, visceral execution of the explosive combat sequences hits home harder than the recitation of the biblical passages. Noted THR in its review, “Gibson’s robust skill as a conductor of large-scale conflict — which goes back to Braveheart — is as sharp as ever. ”.

2017: Atomic Blonde.

Photo : Everett.

David Leitch, yet another former stuntman turned director, and Charlize Theron in stiletto heels, team up for a series of ludicrously inventive, non-stop wall to wall (and through walls) fight scenes and body blows. “A long sequence in the third act, in which Lorraine fights her way through an apartment house’s stairwell, is one for the ages, a bring-the-pain endurance test in which opponents seem nearly impossible to kill,” wrote THR in its review. “Theron punches through it with a fierceness to match Min-sik Choi in Oldboy or Matt Damon in the Bourne franchise. ”.

2018: Deadpool 2.

Photo : Everett.

A reminder that stunt work is always a dangerous business: stunt woman Joi “SJ” Harris died in a motorcycle stunt gone wrong during production. The eventual tentpole, however, proved a critical and commercial smash, and THR‘s reviewer noted: “There’s action aplenty throughout the film, but Deadpool 2 doesn’t bog down in it as many overcooked comic-book sequels do. With Reynolds’ charismatic irreverence at its core, the pic moves from bloody mayhem to lewd comedy and back fluidly, occasionally even making room to go warm and mushy. ”.

2019: Ford v Ferrari.

Photo : Merrick Morton/Twentieth Century Fox.

James Mangold’s period piece is suitably nuts and bolts back at the shop and on the speedway, with the featured models, the supporting vehicles, and the cinematic technique staying true to the 1960s setting.

2020: Tenet.

Photo : Warner Bros. Pictures.

Filmmakers have been rewinding film to make things go backwards since Thomas Edison: not Christopher Nolan, whose stuntmen performed their moves backwards and forwards in real space. He also blew up a real Boeing 747. “Tenet makes you feel floaty, mesmerized and, to an extent, soothed by its spectacle — but also so cloudy in the head that the only option is to relax and let it blow your mind around like a balloon, buffeted by seaside breezes and hot air,” THR noted in its pandemic-era review.

2021: Spider Man: No Way Home.

Photo : MARVEL.

It helps if your stunt doubles can be hidden in a full body costume and mask, as Tom Holland good naturedly acknowledged when he thanked stunt men Luke Scott and Greg Townley. “From Luke’s crash into the stairs to Greg’s falling through the floor to me stubbing my little toe on the glider,” he said at the end of the shoot. “It’s been an adventure. ”.

2022: Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.

Photo : Everett.

In a year of Cameron (Avatar: The Way of Water) and Cruise (Top Gun: Maverick), Ryan Coogler’s sequel is the sentimental selection for its seamless blend of CGI and real-geography action, especially on, in, and under the water.

2023: Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning.

Photo : Everett.

No way to avoid making any list of Hollywood stunt work top heavy with the antics of Tom Cruise. The motorcycle-skydiving leap off a cliff into oblivion is widely considered to be on a par with anything concocted by Buster Keaton or Yakima Canutt, and you’ll get no dissent here.